Earlier this week I attended a MDeC organized private meeting with Richard Stirling from the Open Data Institute (ODI).The ODI is an institution that hopes to promote the ‘open data’ culture, and founded by a giant of the Tech world, Sir Tim Berners-Lee, which you might remember for inventing a small little thing we call the world wide web.

Earlier this week I attended a MDeC organized private meeting with Richard Stirling from the Open Data Institute (ODI).The ODI is an institution that hopes to promote the ‘open data’ culture, and founded by a giant of the Tech world, Sir Tim Berners-Lee, which you might remember for inventing a small little thing we call the world wide web.

The meeting was attended by just a handful of folks, some of whom I recognized from a previous Seatti conference I attended, with the audience and topic focus on Open Data (and Big Data) in Malaysia.

The conversation was really good, and broadly speaking touched on 3 key topics. Most of this post is a re-hash from my failing and aged memory, but there’s a clearer version of the minutes here from the amazing people of Sinar Malaysia if you’re interested in the specifics.

Topic 1: Governments reluctance to Open up data.

Firstly, the Malaysian government is the biggest repository of data in the country, but its reluctant to share access to those repositories with the general public. Some participants shared their difficulties in trying to pry data from the cold hands of Government (both BN and PR) and the disappointment and frustration was quite evident. However, things are changing, and even some in government have seen the light, and slowly but surely the cold hands of government are warming up.

For example the data.gov.my initiative is an amazing ‘little secret’ of MDEC. 3 months ago, I didn’t even know such a website existed, and today you can download dengue statistics, accident rates, etc from a central website that is publishing useful and relevant data most of which are in formats that even the average joe rakyat can process with a copy of Excel. However, some of the data still isn’t up to spec, for instance the Dengue statistics seems to be missing for [tk], but according to MDeC there is a commitment from the relevant government departments to at least keep updating what is published, which is a one giant leap forward from where we were 2-3 years ago.

Topic 2: How to ally concerns of Government

The second key topic discussed was about how to ally the concerns of Government, so that they would be more open. The answer I guess depends on why you think the government isn’t sharing the data in the first place, is it from fear of having the data mis-represented, or fear of revealing private data of citizens or just a lack of demand for the data. Why go through the trouble of publishing the data if nobody ever wants to see the historical API readings across the country?

Ultimately, my ‘political’ view is that the BN government has always held firm control of the media in this country. This is after all a nation where you can’t talk bad about ‘any’ government on television, and the Government is really having a hard giving up the ability to control the public narrative. If raw data is given freely to the public, than anyone can transform that data into a narrative that may be something the government won’t be too pleased about.

I guess the fear is that the more data published, the easier it becomes to cherry-pick data points to support your argument, whatever that argument is pro or anti government. And of course in our country where everything quickly descends into that ghastly realm of politics, that is a very valid concern.

However, this is true of any data-set sufficiently large and complex. Stock analyst looking at near identical pieces of data, can come up with different recommendations for the exact same stock (Buy, Sell or Hold), because they’re taking into account hundreds of different criteria, weighting those criteria differently, and finally combining data with gut-instinct to produce a recommendation.

But while we can’t avoid the possibility of data being mis-interpreted or mis-represented, we can mitigate the risk by releasing even more data!!

This sounds a bit ironic, but it was a great point brought up by a participant at the meeting, which mentioned something along the lines of releasing more data, so that you can ‘iron’ out the edge cases and make it harder for someone to create a narrative that the data doesn’t support.

If you have 97 data points that support an argument, but only 3 that refute it, then you can be pretty confident with a decision based on those 97. Even if the data points were split was 50/50, and half of the data-points supported the argument, while the other half denied it, then at least it’s clear that you should hold off on any action. When you have 100 data-points, making a decision is easy, it’s much harder if you had just 5, or 3, or 1.

The more data you have, the clearer your thinking can become, and the more confident you can be of having ironed out those outliers, that are exceptions to the rule rather than the rules themselves.

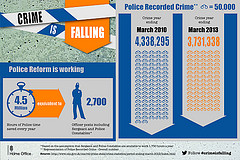

The second key consideration discussed by the group, the sensitivity of the data, specifically with regards to politics. Although not explicitly stated in the meeting, we all know of things like Bumiputera equity, Crime statistics and even the poverty line are all subject to political debates, on which political careers are made or destroyed. Releasing this sort of data would help shift the discussion from anecdotal stories to real-hard facts, which would be great but not entirely realistic, the political resistance to such an action would be too great to overcome.

But if we took weather data for example, which isn’t all that political maybe we could get somewhere. If we could convince the government of releasing these ‘less sensitive’ elements and hopefully value can be created from that data. If you’ve got a killer-app that uses these less ‘sensitive’ data points, then the argument to begin releasing the more ‘sensitive’ data becomes far stronger. My gut-feeling was that MDeC was challenged in trying to demonstrate the value of open data to the government agencies–if there simply aren’t that many people building apps from the data already released…why would the government agencies bother to release more?

The final bit though, was a point raised by Richard himself, when asked how the UK overcame this challenge. When the UK government released crime statistics, the results that it had on house prices wasn’t as dramatic as most people thought, and a lot of people thought it would be a catastrophic near Armageddon effect. I didn’t bring a laptop to the meeting, so all of this is paraphrased from memory:

“You can sense the level of Crime in an area by just being there, and most house buyers already do their homework before hand. Publishing the data, and making it public isn’t going to affect house prices, but it is going to help the public make better decisions. Releasing the crime statistics didn’t end the world”

Here’s an interesting article from the Guardian addressing that very question.

As a last point, a participant at the meeting also reminded that “governments are not just incentivised by ‘social good’ of open data: they can save a lot of money by releasing data (i.e. better apps can be done by community/commercial than in-house); and that commercialisation of open data means increased tax revenue. UK public transport data was a good example.” You know what they say, the one thing true of ALL governments is that the best records, are tax records.

Topic 3: Privacy Concerns

Though not a major topic of discussion, this was one I was intrigued in. I remember the big Netflix debacle, when Netflix released customer data as part of a competition to build a better algorithm to predict which customers would like which movies, only to find out later that by revealing gender, age and zip code of a customer, contestants could uniquely identify that customer. A lesbian mother filed a lawsuit against Netflix, claiming the information Netflix leaked about her, revealed her sexual orientation , which she wasn’t open about.

Though not a major topic of discussion, this was one I was intrigued in. I remember the big Netflix debacle, when Netflix released customer data as part of a competition to build a better algorithm to predict which customers would like which movies, only to find out later that by revealing gender, age and zip code of a customer, contestants could uniquely identify that customer. A lesbian mother filed a lawsuit against Netflix, claiming the information Netflix leaked about her, revealed her sexual orientation , which she wasn’t open about.

Richard quite excitedly shared that there were algorithms and processes to prevent such data leakages, to make sure no ‘edge’ cases were made. The process would automatically identify if the information was too specific, and aggregate it out. This would allow the Government to still be open about the data, yet not reveal personal information.

So for example in prescriptions in Government hospitals were made public and you were an edge case, meaning you were the only Malaysian with leukaemia, hypertension and diabetes, your prescriptions data would be aggregated into the data-set, so people wouldn’t find out that one person in Malaysia took prescriptions for those 3 conditions, and also got a monthly dose of Viagra.

Conclusion

One of the conclusions I drew from the meetup was that sometimes the value of the data can only be unlocked if it’s published, and you don’t really know how valuable the data can be until it’s put out there for people to utilize.Also, while the governments fear of releasing the data isn’t without merit, there are many examples of how to do this effectively and safely.

And some data you publish might be garbage, and never used, but that’s a small price to pay. You have to kiss a lot of frogs to find a prince, but one prince can pay all the frogs in the world.

As a final thought from myself that I developed as I was leaving the meeting, I think there may be too much emphasis on data. Sure data can help us develop policy, and provide insight but people don’t make decisions based on data.

If everyone were rationale, data-driven creatures, no one would smoke, or drive while texting, or deny climate change. Human beings are driven primarily by emotion with data a secondary driver that comes in a distant second.

In my view, data is an important first step, and it’s great to see MDeC and ODI work towards making that data available. However, that data ‘open-ness’ must be followed up by a narrative that makes sense of the data in a way that lay people can understand, and appreciate enough to change.

Afterword

The lovely people at MDeC have a big Data initiative, and they’ve even got a cool little program that helps you work your way into becoming a data scientist, it looks tempting enough for me to try 🙂

Also, attending the meeting motivated me to revisit, and update two of my past projects.

Project 2 : All API readings for Malaysia. (now updated for readings up to 31-Mar-2015)